Accelerating Preclinical Discovery Using “Twin” Data: Validation and Benchmarking on the Pediatric Crohn’s Disease (RISK Dataset)

Executive Summary: Omics datasets—especially transcriptomics—have become foundational in modern biopharma because they connect mechanism to phenotype at scale: they help identify targets, stratify patients, define pharmacodynamic response, and discover safety signals. The challenge is that “omics-ready” data sharing is often the slowest step in the workflow. Patient-level genomic signals are difficult (and sometimes impossible) to truly de-identify with traditional masking or perturbation, so programs frequently default to restricted access, limited collaborations, or long timelines for approvals and contracting.

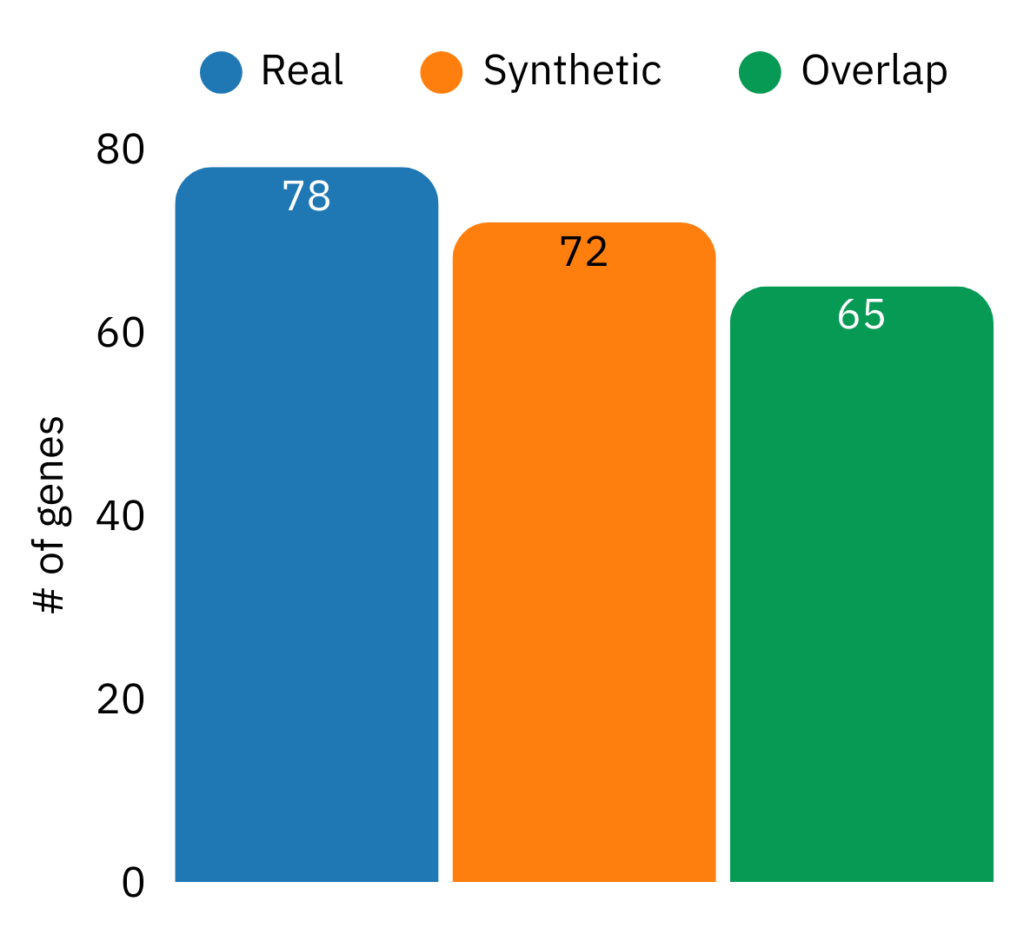

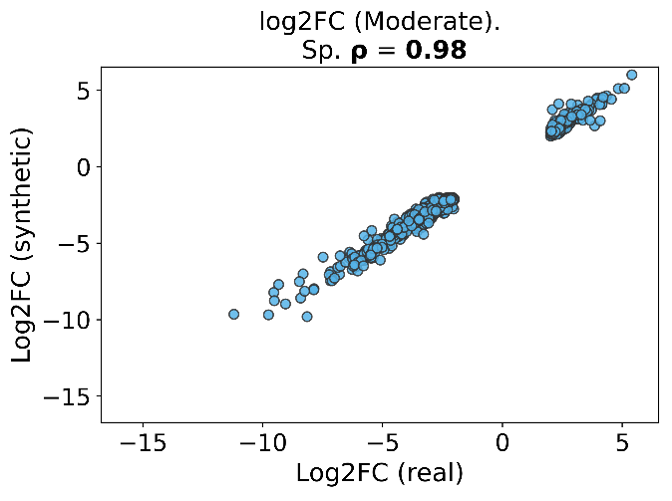

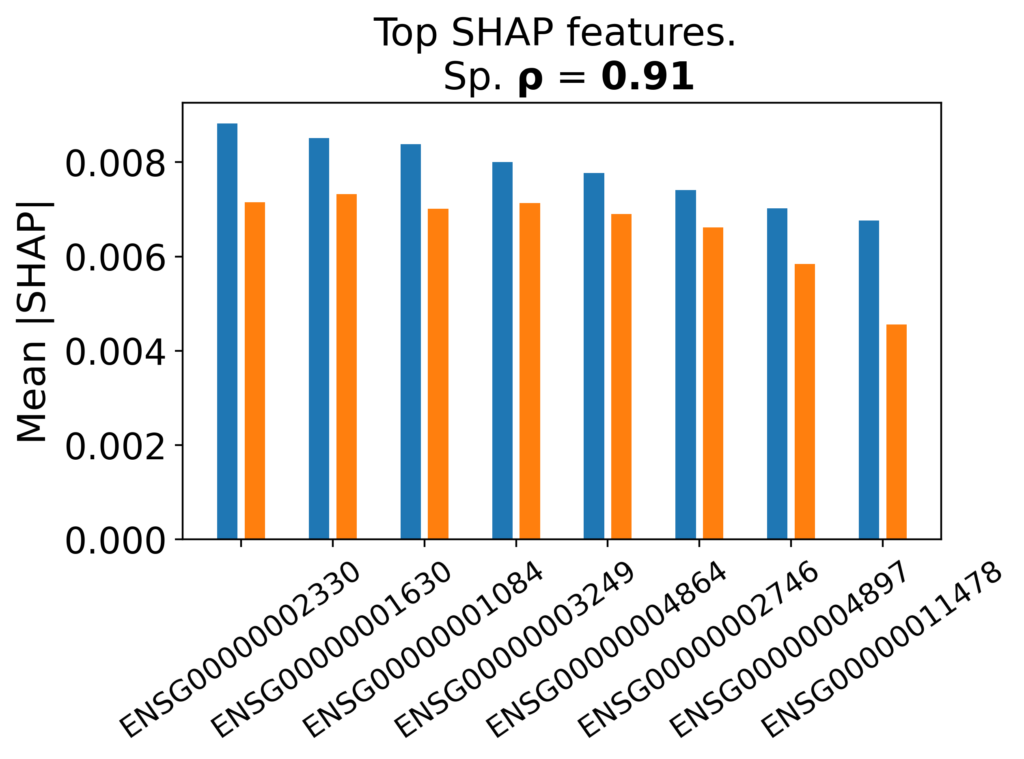

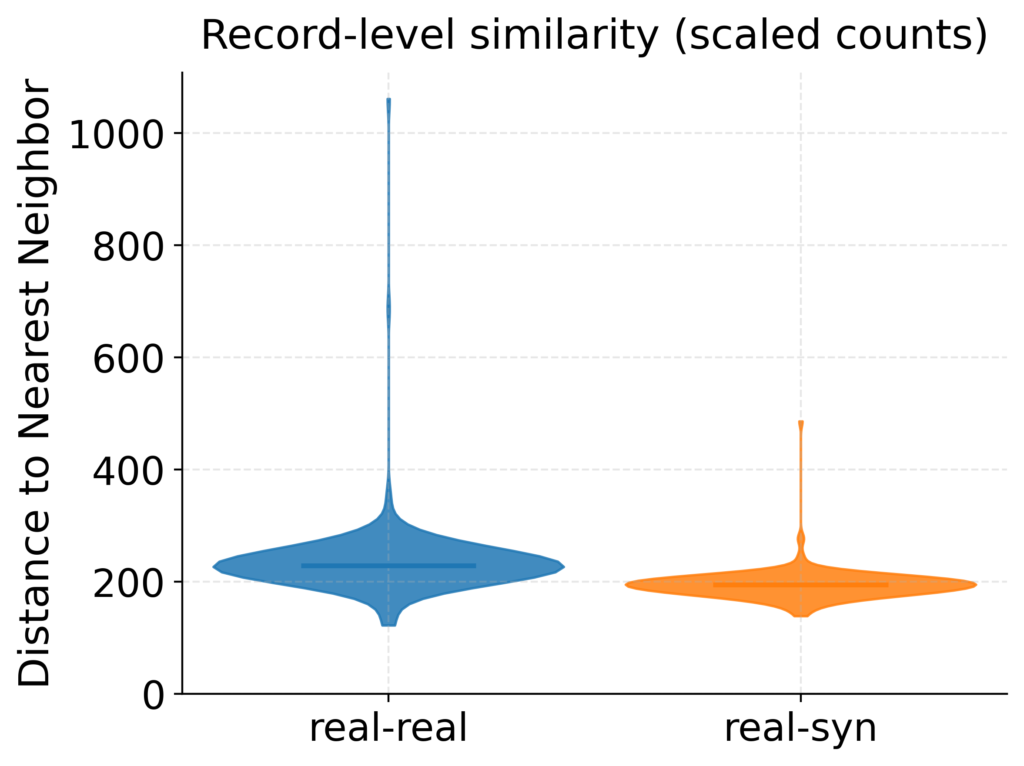

dbTwin addresses this bottleneck by generating synthetic “twin” clinico-genomic cohorts that preserve the structure and downstream analytical value of the original transcriptomic dataset without being linked to individual records in the source dataset. Using publicly available data from the RISK cohort (Pediatric Crohn’s), we show dbTwin synthetic cohorts closely match real data across differential expression findings and log2 fold-change concordance (Figures 2 & 3) and preservation of top predictive biomarkers and feature importance patterns (Figure 4). To address concerns about privacy and memorization of individual expression profiles, we use nearest neighbor distances between real and synthetic samples to demonstrate that synthetic samples are substantially diverse from real (Figure 5). Together, these results support a simple promise: share more, share safe, move faster, and preserve scientific fidelity—without asking teams to trade off utility for privacy.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction: Omics technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) compress an enormous amount of biology into a measurable, model-able space and power several of the most valuable translational loops in R&D by linking pathways to disease biology.

Clinico-genomic omics datasets are extremely useful throughout the entire drug discovery/development lifecycle. In pre-clinical target discovery and validation, high quality case-control transcriptomic datasets are crucial. Clinico-genomic datasets are governed not just by “privacy best practices,” but by a layered ecosystem. IRBs and informed consent set boundaries on how biospecimens and derived molecular data may be reused or shared, while Data Use Agreements (DUAs) define who can access the data, where it can be hosted, and what is permitted, often limiting redistribution, linkage, or downstream sharing.

Crucially, genetic and genomic information is not like ordinary tabular clinical data. Even if you remove direct identifiers, the biological signal itself can remain identifying or linkable, and reviews of genetic privacy have documented multiple routes by which re-identification or sensitive inference can occur when genomic information is shared (Erlich and Narayanan, Reference 2).

Figure 1: Schematic of dbTwin workflow. Real omics datasets (RNA-seq counts) are used as “input”. dbTwin learns a statistically faithful, privacy-preserving model of the data. High-fidelity synthetic cohorts are the output.

Figures 2 & 3: Comparative differential expression (RISK Pediatric Crohn’s dataset)

Figure 2: Counts of significantly differentially expressed genes under moderate stringency criteria in real and synthetic cohorts, with substantial overlap.

Figure 3: Gene-level log2 fold-changes on overlapping genes showing strong concordance between real and synthetic data (Spearman ρ = 0.98).

This is not just theoretical—many organizations treat genetic data as a special case. Novartis’ anonymization standards for patient-level clinical trial data explicitly state that genetic data will not be shared at all, reflecting a conservative stance on privacy risk and re-identification potential (Novartis, Reference 4). Similarly, Roche’s data ethics principles emphasize privacy, consent, and responsible data sharing across the data lifecycle, including genomics-focused initiatives, highlighting how leading biopharma organizations treat trust and stewardship as central to sustainable innovation (Roche, Reference 3). The practical result is that even when a dataset is scientifically “ready,” sharing it broadly, whether internally across teams or externally with partners, can be slow, expensive, and heavily constrained.

Synthetic data is particularly relevant for genomics because traditional de-identification works best when sensitive attributes can be removed while leaving the remaining data useful. In genomics, the biology itself is often the sensitive attribute, and as a result many organizations restrict access rather than attempt “lightweight” de-identification (Erlich and Narayanan, Reference 2). dbTwin’s goal is to shift the sharing conversation from “Can we redact enough?” to “Can we share a faithful twin that preserves the science?”

Privacy-preserving synthetic data has already proven valuable for tabular healthcare datasets, where it enables safer testing, training, and rapid prototyping without exposing raw patient records (Conditional Tabular GAN, Reference 6). The problem is that many deep-learning approaches struggle when you move into omics-scale matrices with 20,000+ features, and they typically require thousands of samples to train reliably. Against that backdrop, dbTwin is built specifically for omics: it uses a non–deep learning generative approach, scales to roughly 80,000 columns, and can produce useful synthetic cohorts even when the source dataset is small—down to about 50 samples.

Here, we use the publicly available RISK dataset to benchmark the analytical utility of dbTwin generated synthetic genomic cohorts. The RISK pediatric Crohn’s cohort (GSE57945) captures ileal transcriptomic profiles from children evaluated for inflammatory bowel disease, making it a uniquely valuable resource for understanding early disease biology and for discovering biomarkers that can guide stratification and treatment. In pediatric Crohn’s, sample sizes are harder to grow, biospecimens are more sensitive, and access is often tightly—so discovery efforts can be limited by who can analyze the data and how quickly collaborations can form. High-fidelity synthetic cohorts like this may help remove that bottleneck by enabling broader, faster iteration on differential expression and biomarker workflows while reducing the need to distribute raw patient-level omics matrices.

Figure 4: Preservation of top machine-learning biomarkers in synthetic cohorts. Comparison of mean SHAP values for the highest-ranking features in the RISK pediatric Crohn’s dataset. Synthetic cohorts closely match real data in both feature ranking and effect size, with strong Spearman correlations computed over the top 200 features.

Figure 5: Row-level similarity between real and synthetic samples. Violin plots show nearest-neighbor distances in scaled expression space for real–real and real–synthetic rows. Real–synthetic distances closely track real–real baselines, indicating that synthetic samples are not overfit/memorized versions of real transcriptomic rows.

dbTwin validation: dbTwin is designed for one core outcome: enable meaningful transcriptomics data sharing without distributing the original patient-level omics matrix. Figure 1 illustrates the operational pattern: starting from a labeled transcriptomics matrix (e.g., Case/CTRL plus thousands of gene features), dbTwin produces synthetic cohorts with the same schema, supporting common downstream workflows while reducing exposure of the original records.

We summarize results for the RISK pediatric Crohn’s ileal transcriptome cohort (GSE57945) (NCBI GEO, References 5). The benchmarks focus on two key questions that matter for translational teams: whether synthetic cohorts preserve 1) differential expression gene-sets and 2) ML biomarker signals (which specific genes drive predictions). Separately, we also look at record-level similarity between real and synthetic rows to ensure that synthetic rows are not simply memorizing or overfitting real records.

Differential expression (DE) remains one of the most common “first analyses” in translational transcriptomics, and a synthetic cohort is only useful if it preserves significant genes and whether effect sizes agree in direction and magnitude. In Figure 2 (RISK pediatric Crohn’s), using the moderate stringency criteria, we obtained 78 significant genes in the real cohort, 72 significant genes in the synthetic cohort, and 65 overlapping genes. Effect sizes on overlapping genes again show strong agreement with Spearman ρ = 0.98 (Figure 3), indicating that even in a smaller DE signal regime, synthetic cohorts maintain gene-level effect structure.

In applied translational ML, it’s not enough for performance to match; teams need confidence that models trained on synthetic cohorts rely on the same biological drivers.

Synthetic-trained models had a relative accuracy of (AUC syn = 0.858 vs 0.863 for real) when tested on hold-out data. Figure 4 compares mean SHAP values for top-ranking genes from logistic regression models trained on real vs synthetic counts and evaluated on a hold-out test set (hold-out not used for training). The key fidelity metrics from Figure 4 are Spearman correlation over the top ~200 features at ρ = 0.91 supporting the interpretation that dbTwin preserves both the ranking and effect-size scale of the most influential transcriptomic features.

Lastly, to evaluate that dbTwin is indeed generating new samples and not simply memorizing real data, we computed nearest neighbor record-level distances between real-syn (contrasted with real-real distances). Figure 5 evaluates nearest-neighbor distances in scaled expression space for the RISK pediatric Crohn’s dataset. The real-synthetic distance distributions closely track the real–real baselines, supporting the interpretation that dbTwin synthetic samples diverse data that do not involve memorizing or overfitting on source dataset. This is critical for data-sharing initiatives where it is crucial that transcriptomic signatures corresponding to real patients in the source dataset do not leak into the synthetic data.

Conclusions: Omics drives modern biopharma—but its full value is often gated by privacy constraints that are particularly strict for genomic and transcriptomic data. The four figures in this report show that dbTwin Genomic can generate synthetic transcriptomic cohorts that are faithful where it matters most: DE signals overlap strongly and log2FC effects remain tightly aligned (Figures 2-3; Spearman ρ = 0.98), top predictive genes and their influence are preserved (Figure 4; Spearman ρ = 0.91), and that synthetic cohorts do not memorize or retain patient expression profiles from the real data (Figure 5). In short, dbTwin helps teams share more biology, with less friction—while keeping privacy and stewardship central to the operating model.

References

- FDA — About Biomarkers and Qualification (BEST biomarker categories). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biomarker-qualification-program/about-biomarkers-and-qualification

- Erlich Y, Narayanan A — Routes for breaching and protecting genetic privacy (arXiv:1310.3197). https://arxiv.org/abs/1310.3197

- Roche — Roche Data Ethics Principles (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd). https://assets.cwp.roche.com/f/126832/x/1b38701897/roche-data-ethics-principles.pdf

- Novartis — Novartis Global Data Anonymization Standards (includes policy note: genetic data not shared). https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Documents/Novartis-Global-Data-Anonymization-Standards.pdf

- NCBI GEO — GSE57945: Core Ileal Transcriptome in Pediatric Crohn Disease (RISK cohort). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE57945

- Xu, Lei, Maria Skoularidou, Alfredo Cuesta-Infante, and Kalyan Veeramachaneni. “Modeling tabular data using conditional GAN.” Advances in neural information processing systems32 (2019).